The Black Land

Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Coal Region

From an area of a bit more than 1,400 square miles in Northeastern Pennsylvania came the power that fueled the industrial age in America. Anthracite has been taken from the ground for more than two hundred years. It broke the dependency on overseas coal and manufacturing, promoted the building of the first canals and railroads, and initiated the birth of large companies with great economic and political power.

At its peak, America’s first gigantic industry was mining 100 million tons each year with over 180,000 people employed. The coal companies formed the United States’ first cartel and executed the first price fixing. Often, they had their own employee housing and stores. Some hired their own police force.

The coal industry dominated all aspects of life in this region. The social fabric was sewn with the layers of immigrants seeking work in the mines. They unionized and fought the companies in the most dangerous occupation of the day.

These photographs are an interpretation of the anthracite region and its history. Each photograph represents a part of the flavor of what is the coal region of Pennsylvania. Each picture has history behind it and alludes to a piece of the total story.

“One Hook Per Man”

Shamokin, PA

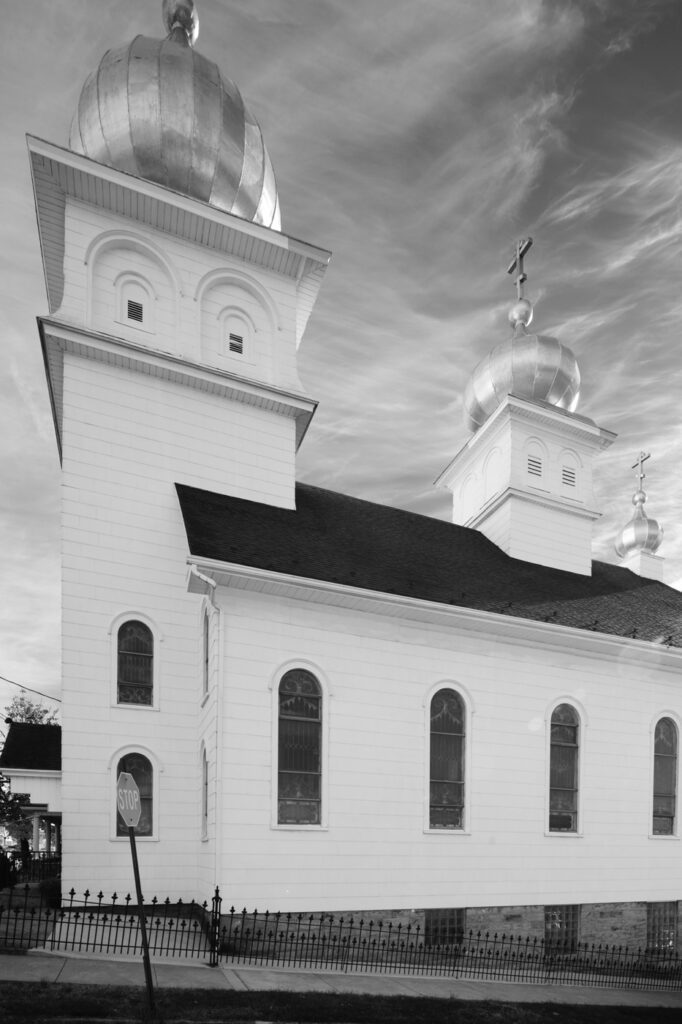

Shrine

Byrnesville, PA

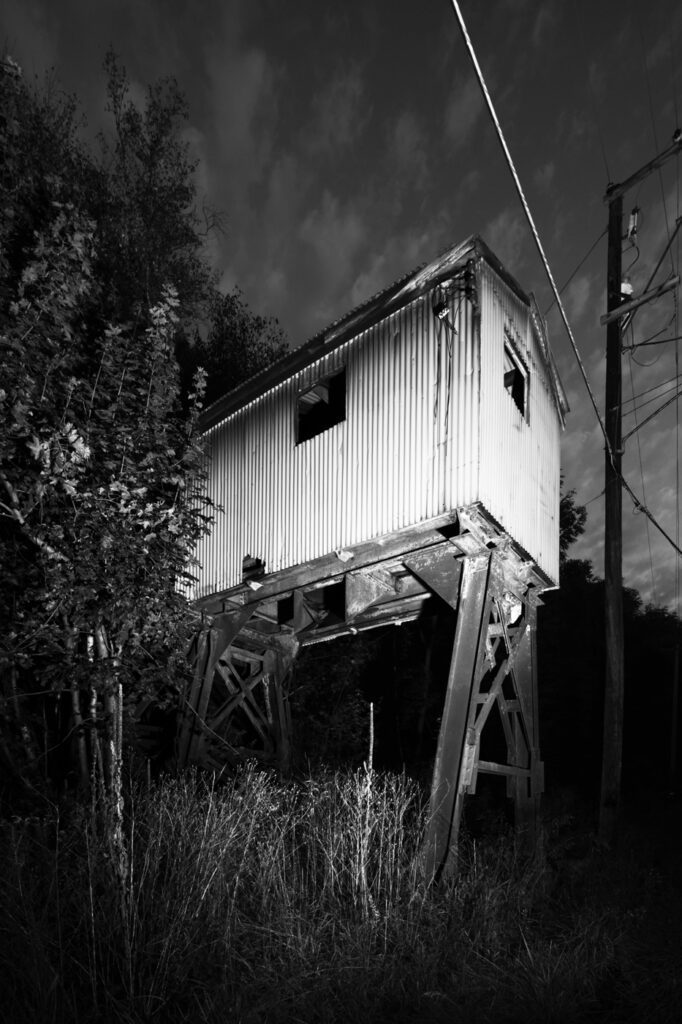

Backyard Coal Breaker

Shamokin, PA

John Siney’s Grave

Saint Clair, PA

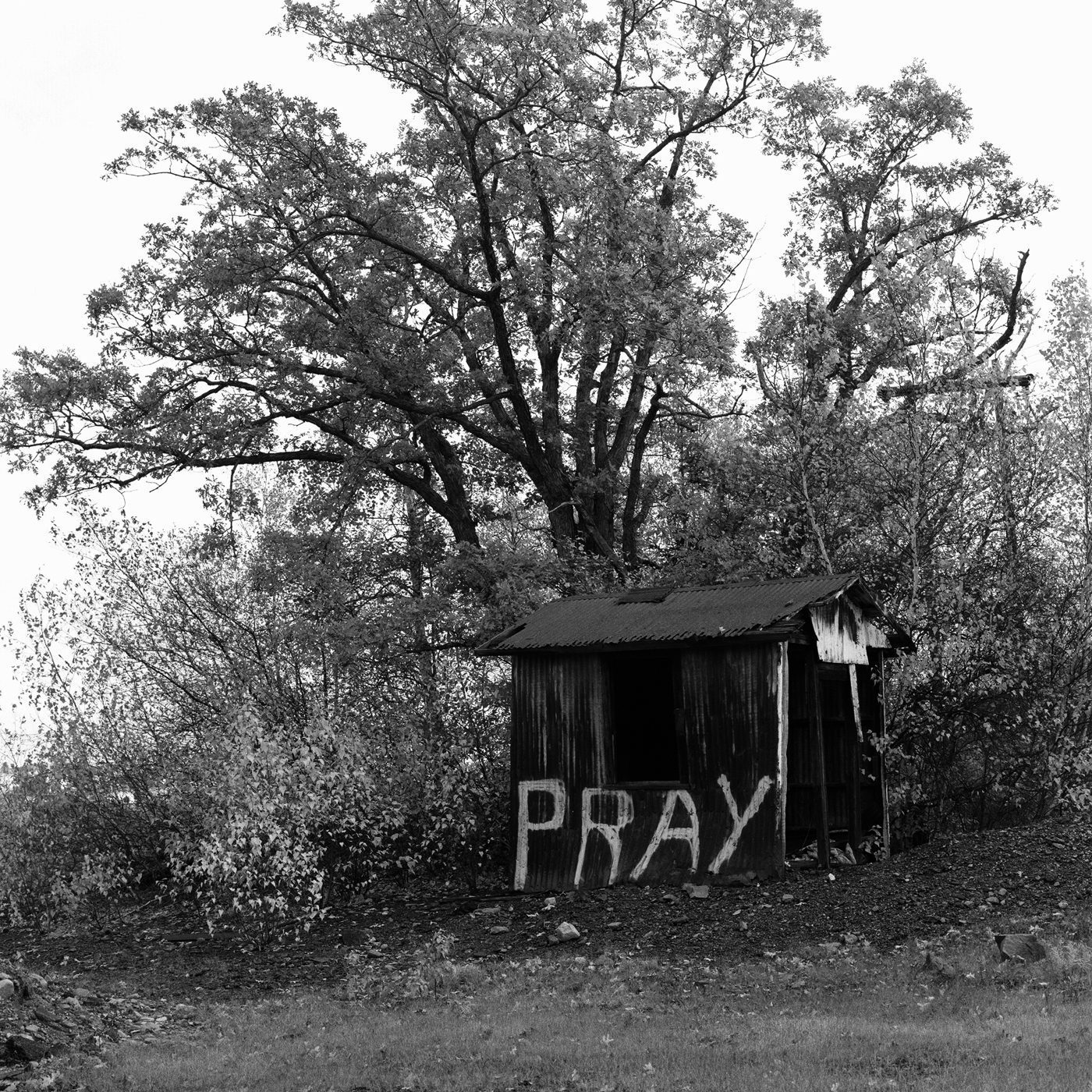

“Pray” – Mine Building

Harwood, PA

Wooden Pipe

Jeddo, PA

Mine Fire Exhaust

Centralia, PA

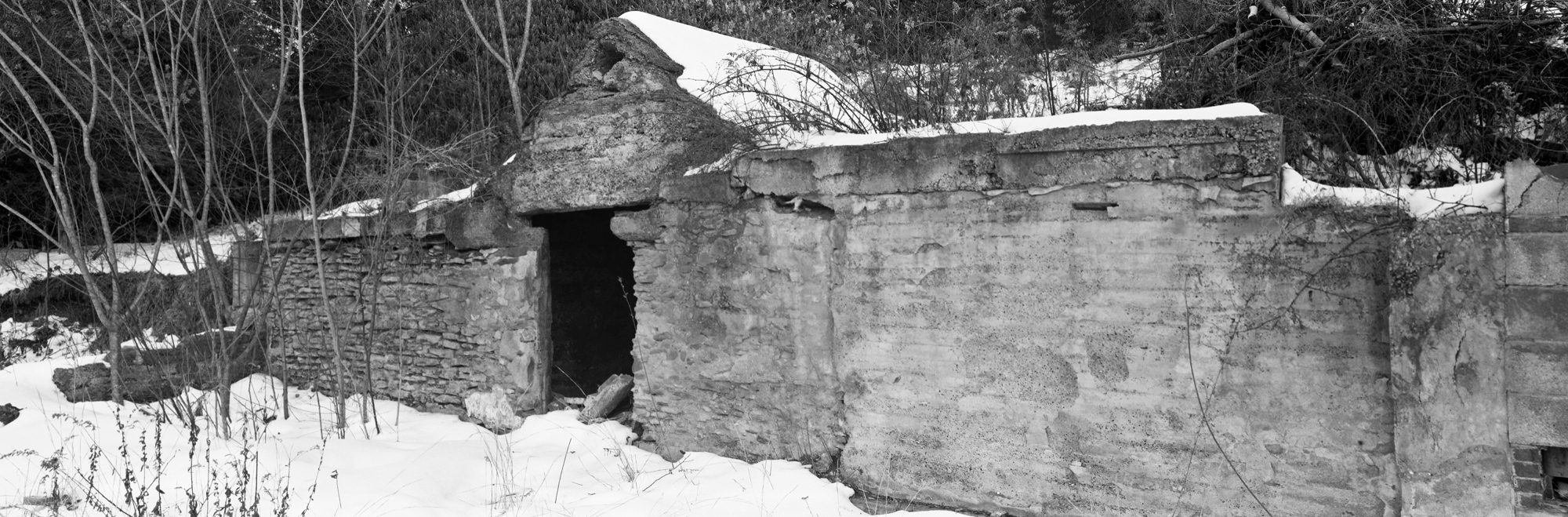

Haunted Grotto

Heckscherville, PA

Hopper Car

Locust Summit, PA

Coal Breaker Rollers

Locust Summit, PA

Mine Waste and Cloud

Beaver Brook, PA

Mahanoy Plane Engine House

Frackville, PA

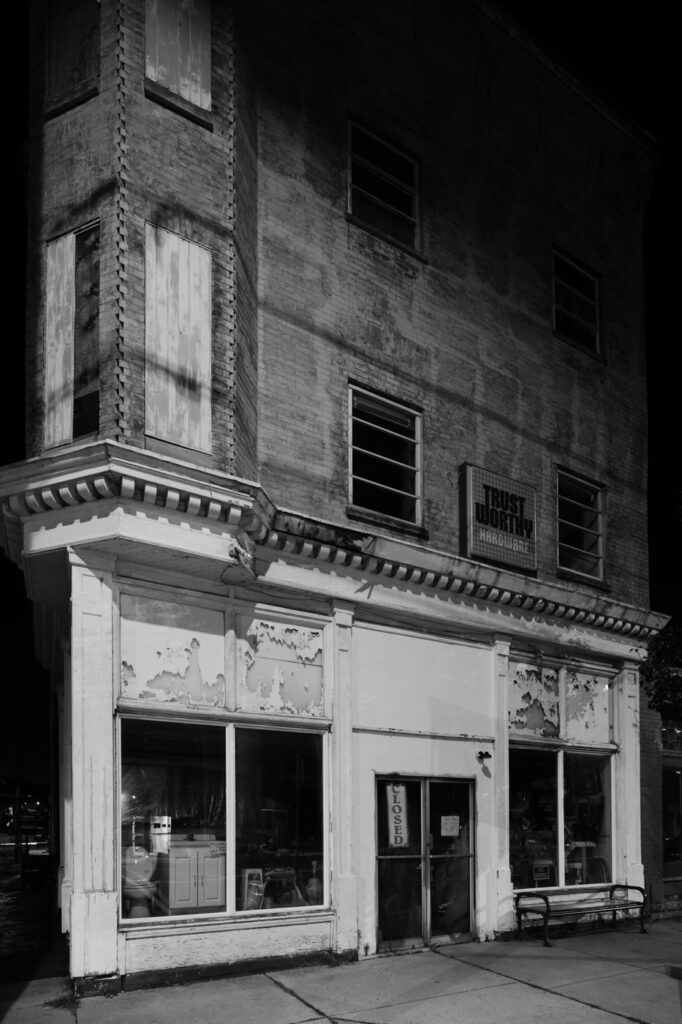

Abandoned Church

Excelsior, PA

Miner’s Homes

Mahanoy City, PA

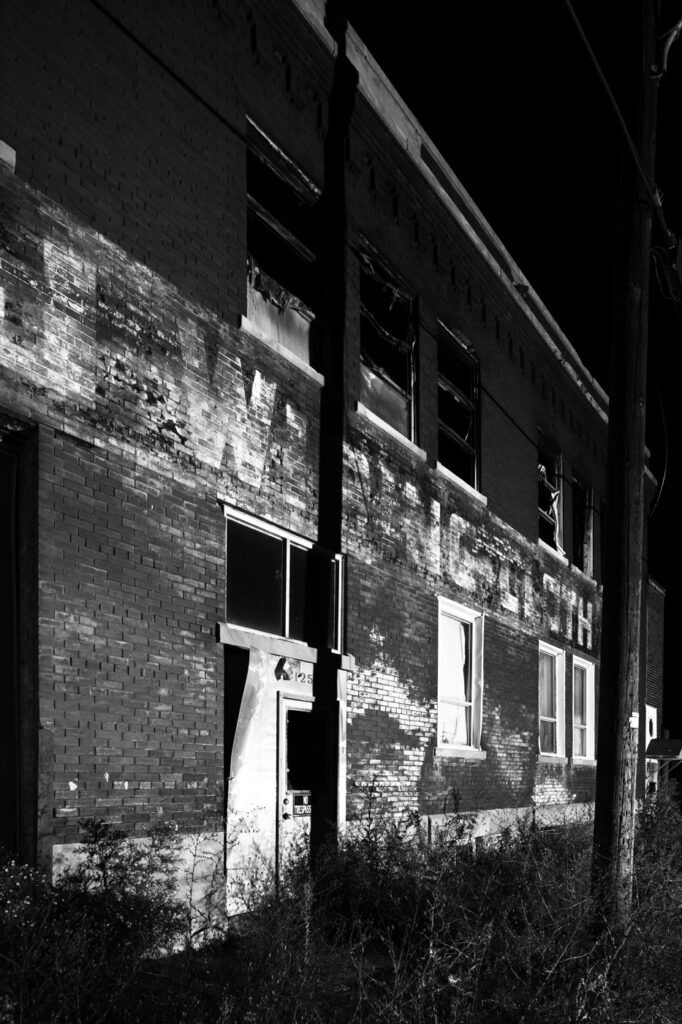

Coal Brook Power House

Carbondale, PA

Locust Summit Breaker

Locust Summit, PA

Mine Entrance

Off the Side of a Road, PA

House of God

Centralia, PA

Exposed Mine Shaft

Locust Summit, PA

Gangway

Lansford, PA

Hereditament

The structures stand proud, as if they remember the years of prosperous, tight knit community, but are saddened by those memories fading in the current economic challenges that the area faces. Companies bankrupt, churches close, homes abandoned but the municipalities often cannot fund the removal of these decaying properties.